Political acceptability is the biggest challenge for ambitious climate policy. New insights suggest that carbon prices are more likely successful if revenues are paid back as dividends to citizens.

Carbon pricing is widely understood as an indispensable tool for meeting the goals of the Paris agreement to mitigate climate change. However, less than 20 percent of current global greenhouse gas emissions are covered by a carbon price and most prices are below the USD 40-80 per tonne CO2 range necessary to achieve the goals pledged under the Paris Agreement. Carbon prices differ widely in ambition and scope across countries, even when macroeconomic indicators are similar. Sweden and Australia, for instance, both had gross domestic products around US$50,000 per capita in 2017. While Sweden currently has the world’s highest carbon price of US$139 per tonne of CO2, Australia has abolished its carbon pricing scheme in 2014 even though it was designed "by the book" regarding criteria of efficiency and equity.

This blog post argues that garnering greater political acceptability is the primary challenge for policy makers when implementing and maintaining carbon pricing reforms. Although traditional lessons on efficiency and equity are important components of acceptability, they are of secondary nature. Carbon pricing reforms could be tweaked to enhance their acceptability to the general public, building on recent insights from behavioural and political sciences. Factors related to public perception, such as the salience of benefits, cultural world views or general trust in politicians, contribute ideas on how carbon pricing could be made more attractive to the public. Since global carbon pricing revenues are already substantial (USD $33 billion in 2017) and are likely to increase in the future, their use plays a major role in the public perception.

What makes carbon pricing popular?

Four major effects emerge from behavioural science regarding the acceptability of carbon pricing reforms. First, the willingness to pay for climate change mitigation is largely a function of political, economic, and cultural world views. Triggering "solution aversion" – the tendency for citizens to be more sceptical of environmental problems, if the policy solution challenges or contradicts underlying ideological predispositions – has to be avoided.

Second, citizens tend to ignore or doubt the corrective (“Pigouvian”) effect of carbon pricing, but may be mollified if revenue is earmarked for a specific purpose such as green spending or transfers to disadvantaged households. Third, the labelling of the carbon price may alter perceptions of its desirability. Something as plain as re-labelling a carbon price as a “CO2 levy”, as done in Switzerland and Alberta, or speaking of “fee and dividend”, could circumvent solution aversion and make the measure more acceptable to citizens. Fourth, increasing the salience of the benefits derived from a carbon-pricing reform enhances acceptability, so that visible revenue recycling may be advisable. Some recycling methods, such as transfers to households or public investment, might be more visible to the public than tax cuts, for instance.

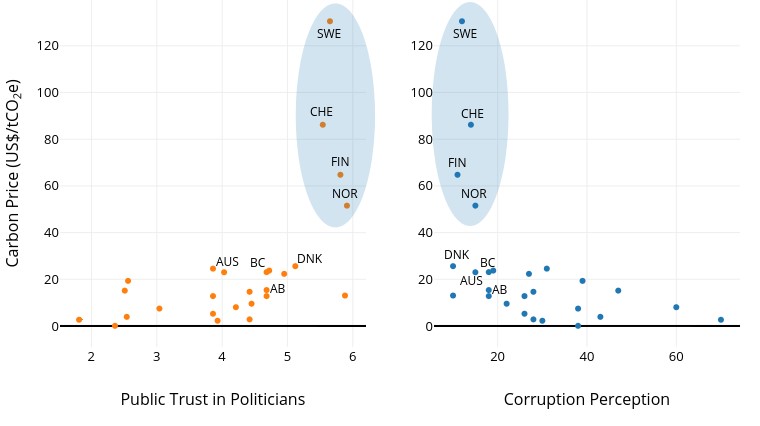

Political science yields two main insights regarding carbon pricing: First, ambitious carbon pricing is often correlated with high political trust and low corruption levels (see Figure 1). Cross-country studies indicate that countries with greater public distrust of politicians and perceived corruption persistently have weaker climate policies and higher greenhouse gas emissions. This is exemplified by Finland, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland which all exhibit high trust levels and have carbon prices above 40$ per tonne of CO2. If trust is low, revenue should thus be recycled using a transparent, trust-boosting strategy to enhance its acceptability.

Second, a policy reform is more likely to be successful, if its costs are diffused and the benefits are concentrated. The challenge with carbon pricing is that it tends to have diffuse benefits and concentrated costs. So the scattered beneficiaries of the policy are less likely to support it in the political process than carbon-intensive companies are to oppose it. Success may be more likely, if the benefits of carbon pricing reform are concentrated on constituencies who will actively support the policy’s passage and preservation. Additionally, carbon pricing schemes are more likely to survive successive partisan changes in government, if they benefit constituencies across the political spectrum.

Which design strategies enhance the political acceptability of a carbon tax reform?

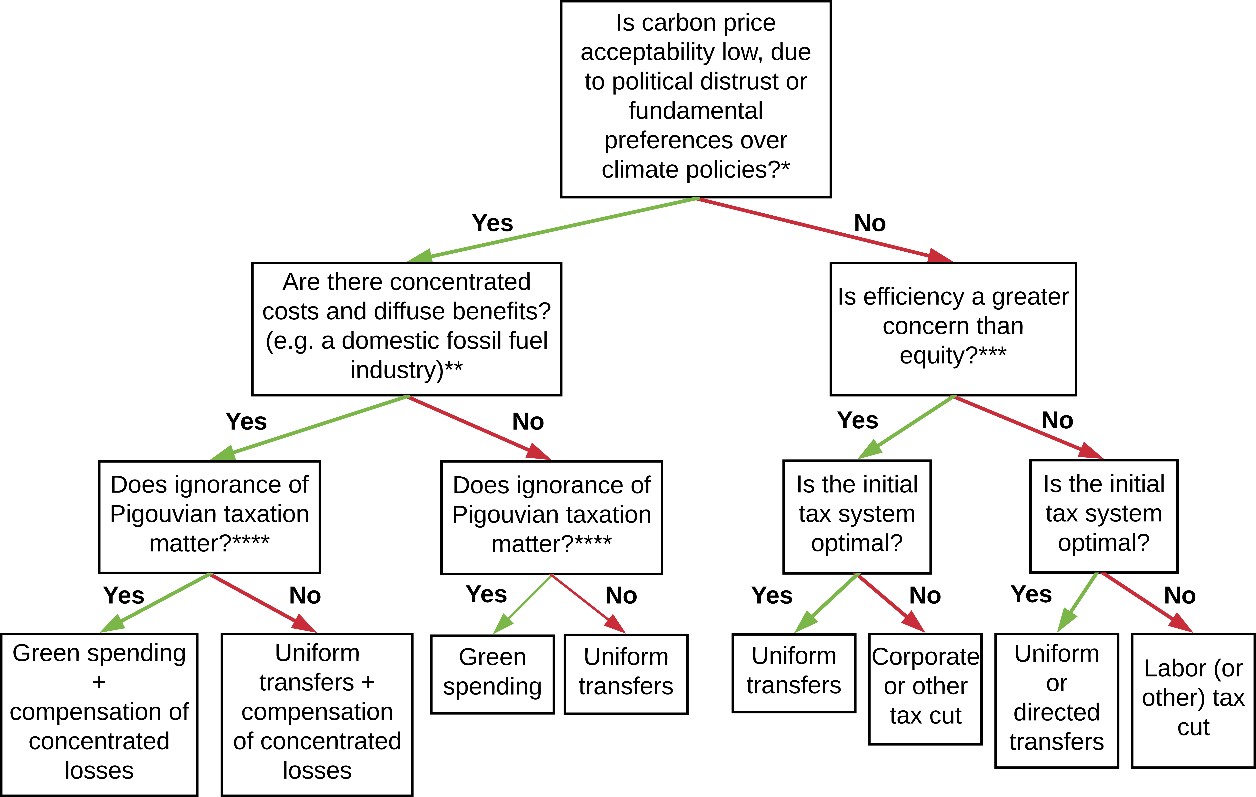

Apart from careful labelling, making sure that the benefits are salient, avoiding solution-aversion and ensuring transparency and clear communication, the acceptability of a carbon tax reform can be further enhanced by adapting the revenue recycling strategy to the socio-economic context (see Figure 2): While recycling revenue as lump-sum dividends addresses most behavioural and political constraints on carbon pricing, other recycling methods such as green spending, targeted transfers or tax cuts can be more appropriate, depending on the socio-economic context.

If citizens question the mitigation impact of Pigouvian pricing, for example, increasing green spending might convince them of the policy reform. Earmarking the revenue to address specific salient problems such as underfunded pension schemes or crumbling infrastructure could also enhance the acceptability. Inequality concerns should be addressed by directed or lump-sum transfers, which would predominantly benefit poor households as they receive more in transfers than they spend on carbon taxes. If efficiency is a major concern, using the revenue to reduce other distortionary taxes is the preferred option. Budget-neutral strategies such as uniform transfers or tax cuts are more appropriate in contexts of prevalent centre-right world views, low-trust governments and tax aversion.

What can be learned from real-world carbon pricing schemes?

Armed with these insights, we can now better understand the example from the beginning of this post: The success story of Sweden’s world-leading carbon tax may partly be owed to extensive public dialogue and social deliberation. This may have reinforced political trust and transparency prior to the fiscal reform that introduced carbon taxation. The Australian carbon pricing scheme provides a cautionary tale. It demonstrates that a carbon price design that meets equity and efficiency goals alone is not sufficient, while politics and political communication are of crucial importance.

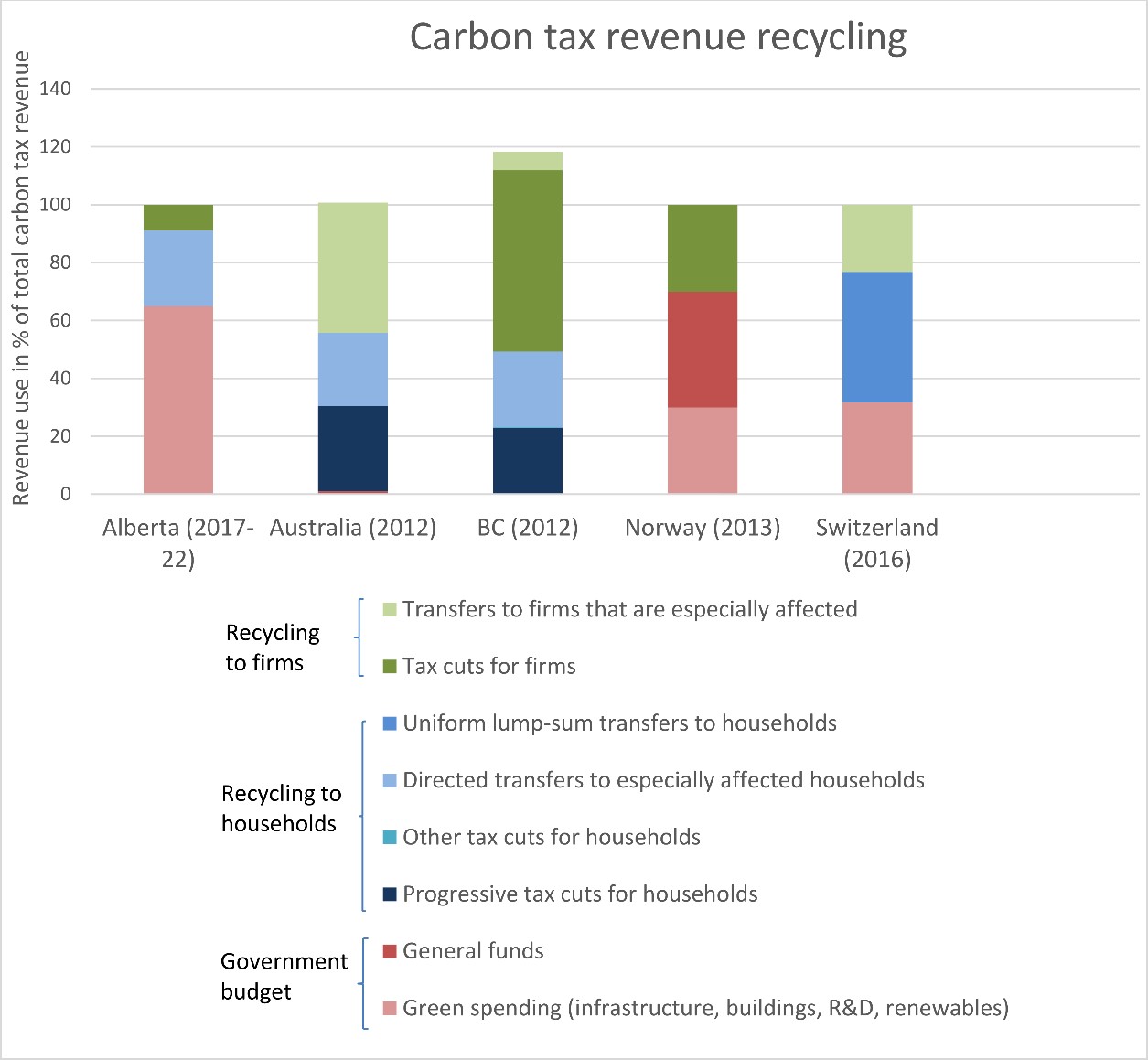

Successful carbon pricing initiatives in other countries have designed their revenue recycling in accordance with at least some of the presented political and behavioural effects (see Figure 3 for an overview of recycling in different carbon tax schemes).The revenues of Alberta’s successful “carbon levy” are split between green spending and compensation for those who are disproportionately affected by carbon pricing, thereby illustrating lessons on labelling and the ignorance of Pigouvian pricing. British Columbia, where all carbon tax revenues go to households and firms, has created strong constituencies in favour of carbon pricing. Backed both by an environmentally aware electorate base and the business community, the center-right government was able to design a carbon tax reform that enjoys broad political acceptance.

Making carbon pricing work - acceptability first, efficiency and equity second

In light of the current carbon pricing gap, economic lessons on efficiency and equity are subsidiary to the primary challenge of garnering greater political acceptability. Redistributing carbon pricing revenue as a regular carbon dividend ticks most boxes regarding political acceptability, although other ways of using the revenue can be appropriate in given circumstances. Revenue recycling mechanisms should be designed with an eye on political and behavioural insights and in accordance with the socio-economic context. This can help make carbon pricing work for citizens.